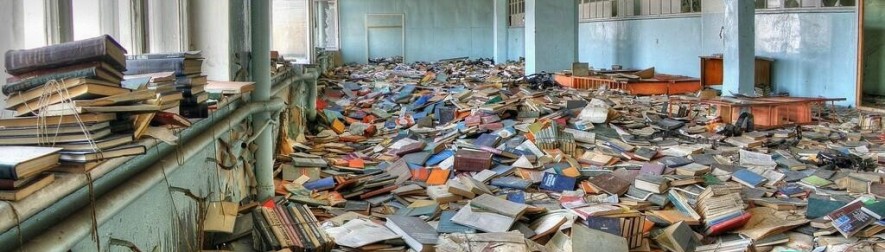

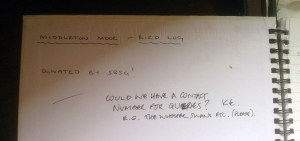

Hidden in a small private woodland, off a public footpath, several miles from any town, overlooking an artificial lake, itself a product of the Derbyshire Dales industrial past, stands a lone wooden shack, barely large enough for four people to stand in. The shack is a bird hide, from which twitchers can monitor the avian comings and goings on the lake. Set into a narrow wooden shelf, beneath the hide’s long, thin windows, is a compass showing the cardinal points. Contained within the hide are two A4 notebooks, in which a log has been kept, a diligent record of the species and numbers of birds frequenting the lake, dating back to 2004. Human beings are natural archivers, recorders, creators and organisers of data, from which, I assume, we must gain a Darwinian advantage over our competitors. The variety of means through which this inclination manifests, as a collector (as well as creator) of narratives, endlessly fascinates me. Also contained within the hide and the notebooks is evidence of behaviour for which the hide was not designed. Sketches and scribblings amongst the sober recordings suggest it is not only bird-watchers who visit the hide. A doodle of a duck smoking a joint hints at other, more illicit, uses.

Thálatta! Thálatta!

On Wednesday, 13th November, 2013 I moved to Aldeburgh on the Suffolk coast, where I rented a small, sea front cottage, until Tuesday, 24th June, 2014. Over those 32 weeks, or 224 days, I took a photograph from the same spot on the beach, directly in front of my cottage, looking out to sea, at roughly the same time of day (usually between 11am and 1pm, depending on what I was doing that day), for every day that I was resident in Aldeburgh. (There are notable gaps in the record, when I was away seeing family, or visiting friends in London, for example.) I was interested in repetition, and discipline. For the first time in my life I was devoting myself entirely to art. I had a little capital, and, for a short while at least, I was not relying on regular paid employment. I had moved to the Suffolk coast to establish myself as a full time artist, my aim to earn a sufficient income from my work.

On Wednesday, 13th November, 2013 I moved to Aldeburgh on the Suffolk coast, where I rented a small, sea front cottage, until Tuesday, 24th June, 2014. Over those 32 weeks, or 224 days, I took a photograph from the same spot on the beach, directly in front of my cottage, looking out to sea, at roughly the same time of day (usually between 11am and 1pm, depending on what I was doing that day), for every day that I was resident in Aldeburgh. (There are notable gaps in the record, when I was away seeing family, or visiting friends in London, for example.) I was interested in repetition, and discipline. For the first time in my life I was devoting myself entirely to art. I had a little capital, and, for a short while at least, I was not relying on regular paid employment. I had moved to the Suffolk coast to establish myself as a full time artist, my aim to earn a sufficient income from my work.

My interest in taking the photographs was, like much artistic practice, simply to see what would happen. If I limited the criteria: the same physical place; a similar time of day, and limited the composition: 50% sea; 50% sky; bisected by the horizon in the middle, what would be the result? How different would the images be? Because, of course, I didn’t take the images in the same place, or at the same time. Space and time are relative. The Earth had moved many thousands of miles in the intervening 24 hours, so had the Sun, and the Solar System, and the Milky Way, all in an endlessly complex interplay of cycles. And it was a different day, with different light and atmospheric conditions. And maybe, it could be argued, I was a different person, with 24 hours worth more life experience, in a different mood, with different brain chemistry. No two moments are the same moment. It is, therefore, no matter how carefully composed and contrived, impossible for any two images to be the same.

The result, Thálatta! Thálatta!, is a series of 168 photographs. The title is taken from Xenophon’s Anabasis, and is the cry of joy made by an army of Greeks upon seeing the Black Sea, and realising that their safety is close at hand after a failed military campaign against the Persian Empire in 401BC. (1) It is a cry echoed in Iris Murdoch’s 1978 novel, The Sea, The Sea. The protagonist of Murdoch’s novel, Charles Arrowby, a narcissistic playwright, has retreated to the coast, withdrawing from the world, searching for the isolation in which he can examine his life and write his memoirs. (2) It was a similar withdrawal which took me to Aldeburgh. It was a wiping of the slate clean. After a failed relationship and stagnant career, I had quit work, quit home, and was starting completely anew. By staring out to sea, by limiting my view, reducing my surroundings to the fundamentals of sky and sea, air and water, I was seeking solace and tranquility, a gathering of strength with which to begin again.

The images in Thálatta! Thálatta! reference the black and white seascapes of Hiroshi Sugimoto, whose own series began when asking himself what contemporary view might early hominids recognise. His answer was the sea, and possibly only the sea. (3) When we look out to sea we find our perception of time is altered, it slows down our present, asks us to contemplate the past, whilst also projecting us into potential futures. What possibilities lie beyond the horizon? Where will I be in a couple of years from now? As Sugimoto says: “Mystery of mysteries, water and air are right there before us in the sea. Every time I view the sea, I feel a calming sense of security, as if visiting my ancestral home; I embark on a voyage of seeing.” (4)

What did I learn from my own “voyage of seeing” in Aldeburgh? I learnt that, as far as I was concerned, worrying about money took all the pleasure out of making art. I arrived at a point where I could no longer allow myself to create something unless there was a visible pay cheque at the end of it. I discovered that the monetising of my practice changed my relationship to creativity to such a degree that I no longer enjoyed it. I saw that attempting to place a financial value on my work resulted in bad art, or even no art at all. Also, I was depressed and running out of money. And so, I left my little sea front cottage, moved back to the hills of the Peak District, my spiritual home where I had not lived for eight years, and began my new beginning again.

And now, with Thálatta! Thálatta!, I complete a work that has been in my head for more than three years, ever since I took the first photograph, at 12:29 on Wednesday, 13th November, 2013. With this work I celebrate my eight months on the Suffolk Coast: the collages made in a sun-filled living room-come-makeshift artist’s studio; the album recorded in the little attic room overlooking the beach; the unfulfilled artist’s residency at Sizewell Nuclear Power Station; the walks and bike rides up and down the coast; the visits to my friends in Debenham, 25 miles inland; the strangeness of the watery landscape (Orford Ness, Shingle Street, Snape, Thorpeness, Dunwich); all this is contained in the 168 photographs of Thálatta! Thálatta! It may look like a sea and sky the same as any other on the planet, but it isn’t. It is a very personal record of a very specific time and place. It is one small, but significant, chapter in an ongoing autobiography.

CJ Robinson, January 2017, Buxton, Derbyshire

1) Xenophon, Anabasis (The Persian Expedition), translated by Rex Warner (Penguin Classics, 2004)

2) Iris Murdoch, The Sea, The Sea, (Chatto and Windus, 1978)

3) Kerry Brougher & David Elliot (eds.), Hiroshi Sugimoto, (Hatje Cantz, 2005)

4) http://www.sugimotohiroshi.com/seascape.html

Thálatta! Thálatta! can be purchased here.

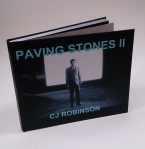

Paving Stones II

In 2001 James Merrick created his abstract graphic novel Paving Stones. Now, sixteen years later, CJ Robinson produces Paving Stones II in homage to his friend, colleague and occasional collaborator. Paving Stones II uses images and text borrowed from … Continue reading

Look and See

Found Narrative No.7

Last weekend I attended a private book sale at the house of a friend’s friend. The house owner’s husband had died a few months ago leaving a library of over 10,000 books and the house owner was in the process of organising the house’s contents in order that she could move forward with her own life, and eventually sell the house. The book sale was a part of this process. The man who had accumulated this library, a retired journalist, had spent the last two decades of his life researching a book, which will now never be written. Many of the books in the sale contained strips of paper with handwritten notes relating to elements of his epic work in progress, giving tantalising hints as to the subject of his unwritten magnum opus. Found Narrative No.7 is one of these books. The notes suggest that the author was looking into that blurred area where science and faith meet, often uncomfortably. The many other books in his library strengthen this suggestion, covering, as they do, subjects such as: physics; cosmology; philosophy; linguistics; astronomy; astrology; ufo’s; mythology; spiritualism; magic; the Western Esoteric tradition; angels; comparative religion; alternative history; and more. When I asked my friend, who has been close to the family for many years, what the curator of the library’s book was to be about, she replied, after a considered pause: “Everything!”

Found Narrative No. 6

Hidden away in the fire place of Dove Cottage, a community venue owned by the church next door, in Debenham, Suffolk, Found Narrative No. 6 is a set of index card drawers containing the hand written record of every birth, … Continue reading

Look and See

The difference between looking and seeing.

By definition, to look is considered to be the more conscious act. We see things that come into our vision, unexpectedly, we look with intent. This suggests that looking is the more purposeful, dynamic activity, involving thought and will. We turn our gaze to a specific thing. Seeing, it seems, can be almost accidental, and does not require thought. But, a deeper meaning of ‘to see’ is to reflect on something and to gain an understanding of something. It doesn’t have to have been visually seen. As in “oh, I see,” it involves a realisation, a moment when we cross a threshold from something unknown to something known. You can look without seeing, but can you see without looking? It is this deeper meaning to which I am referring with the series of installations and photographs Look and See. (I owe a debt to Roy Voss, my tutor from the University of the West of England, where I studied a Masters Degree from 2006 to 2009, whose work I am openly referencing with this series.)

Dream Songs – New Album Released as The Erratic

“When I listen to this music I want to grow a short beard, learn violin, never talk again, learn how to sword fight but vow not to actually sword fight, only have 2 things in my closet; a monks robe and a suit, move to Nova Scotia, Stare out a window on rainy day, ignore my lover, seek love where I know I will never get it, miss my dad, act like everyone is dead, read sad books, gain lots of muscle but never be seen doing physical activity, have a son then learn he won’t live to be 5, be left by my wife, fight to keep her get beaten up by her lover, punch a wall, change my name to Mikol and cry in secret.“

Comment left by Goat Men below ‘Max Richter Infra 2010 Full Album’ on YouTube (1)

Ok, let’s start with the title. The name ‘Dream Songs’ is stolen from a book of poems by the American poet John Berryman. Berryman’s ’77 Dream Songs’, published in 1964, along with ‘His Toy, His Dream, His Rest’, published in 1968, were published together in 1969 as ‘The Dream Songs’. Like Berryman’s ‘The Dream Songs’, ‘Dream Songs’ the album could be easily misinterpreted as autobiography, but as Berryman says of his protagonist Henry: “Henry does resemble me, and I resemble Henry; but on the other hand I am not Henry. You know, I pay income tax; Henry pays no income tax. And bats come over and they stall in my hair—and fuck them, I’m not Henry; Henry doesn’t have any bats.” (2)

Although I look like The Erratic, The Erratic doesn’t have any bats (and, presently, I don’t pay income tax). In 1972, at the age of 57, Berryman, who struggled with alcoholism for much of his adult life, committed suicide by jumping into the Mississippi River from the Washington Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

The structure of ‘Dream Songs’ combines aspects from a number of albums by David Bowie. Like ‘Low’, and repeated on ‘Heroes’ (both released in 1977), the first half of the album comprises ‘songs’ while the second half contains more challenging and semi-ambient instrumentals. The album is bookended by two versions of the same song, as with ‘It’s No Game (Parts 1 & 2)’ on 1980’s ‘Scary Monsters and Supercreeps’. Neil Young also notably did this, with the acoustic ‘My My, Hey Hey (Out of the Blue)’ and the electric ‘Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black)’ on 1979’s ‘Rust Never Sleeps’.

The song ‘Down, Down, Down (Part 2)’ was written whilst on a walk across Kinder Scout, descending Jacob’s Ladder near Edale in the Peak District, Derbyshire. All the harmonies came fully formed as I walked down the steep stone steps that lie near the start of The Pennine Way. ‘Down, Down, Down (Part 1)’ is, more or less, ‘Part 2’ reversed. I was pleased to discover when listening back to ‘Down, Down, Down (Part 1)’ that the reversed guitars resemble the sounds of the guitars on early Eno albums, in particular ‘Another Green World’ from 1975.

‘Holy! Holy! Holy!’ references Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Footnote To Howl’ (1955) (3), which declares everything to be holy. In particular his declaration that every aspect of the human body is holy (“The world is holy! The soul is holy! The skin is holy! The nose is holy! The tongue and cock and hand and asshole holy! Everything is holy! everybody’s holy! everywhere is holy!”). This section of Ginsberg’s poem is an erotic cry of joy and celebration of the physicality of human love. The song ‘Holy! Holy! Holy!’ is a celebration of a lover, and a lament for lost love. It makes the suggestion that maybe the unnamed relationship could have lasted “If I could only believe you…when you said that you loved me.” This sentiment echoes a song written two years earlier, called ‘I Wish That I Could Believe’ (although this song has a more general existential theme), from the EP ‘Eleven Kinds of Loneliness’ (the title of which is again borrowed, this time from a book of short stories by Richard Yates, published in 1962 (4)). The EP, along with all other releases by The Erratic, is available at: http://www.theerratic.bandcamp.com

Much of ‘Dream Songs’ was written and recorded during a recovery from depression, and, rather than a record of depression (that is the ‘And’ EP), should be seen as a document of the difficult ascent out of mental illness. Depression is a daily struggle. Every morning is a battle to see the day through to the end. ‘Gone (Never to Return)’ is about that struggle. Upon first awakening in the morning the depressed see an endless blank stretch of time, an interminable emptiness with nothing to fill it. But soon enough the day has ended and nothing has been done, other than that another day has been survived. The song quotes the first line, spoken by Estragon in ‘Waiting for Godot’ by Samuel Beckett, with it’s multiplicity of meaning: “nothing to be done.” (5) This is the second time I have quoted this line, the first being in the song ‘Let Me Dream’, from the ‘I am a Traveller in Both Time and Space’ EP (itself a reference to William S. Burroughs’ opinion that his use of collage, photography and the infamous cut-ups were all methods of time travel).

In contrast ‘I Would Never Leave This World’ is a declaration of the desire for life. It states categorically ‘I want to live, I will not leave this world by my own hand.’ It still contains regret, and recognition of mistakes made and admits culpability in the same failed relationship as in ‘Holy! Holy! Holy!’ (6): “It was never meant to last. Can I be forgiven? … I gave it all my love, I gave it all to you. … I gave you all my love, and I took it from you.” There is some ambiguity however in the repeated and, to a large degree nonsensical, line: “I would never leave this world with more than I could give it.” It is impossible to give more than you can give. The song references Simon and Garfunkel’s ‘Cecilia’, from their 1970 album ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’, with it’s use of multiple hand claps put through an echo delay. It also uses the same tuning as on the last song Nick Drake ever recorded (in February 1974), ‘Black-Eyed Dog’ – GGDGBD.

‘Ascent (Into Insignificance)’ provides a pivot for the album. It is the first of the instrumentals and introduces new textures with the addition of recorder and saxophone. The guitar plays a number of barred chords in DADGAD tuning (much of the album was recorded in this tuning), randomly layered on multiple tracks. The recorder builds up another chord with long single notes, again randomly layered. This provides a backdrop over which Julian Cohen improvises two takes of saxophone, giving the whole a feel not too dissimilar from Charles Mingus. The only direction I gave was to tell Julian at which point to begin playing. The title is taken from Professor Brian Cox, who in a recent TV series said that the development of human kinds’ notion of it’s place in the cosmos, from believing ourselves to be at the centre of the universe to the realisation that we are the highly unlikely result of an almost endless sequence of chance happenings that occupies a tiny insignificant point in an infinite universe, could be described as an “ascent into insignificance”. (7)

As mentioned on the sleeve notes, ‘Dead Star Light‘ was recorded live in a single take and no overdubs. It was made using an electro-acoustic guitar and a Line 6 amp with a rudimentary built-in loop facility. Production and mixing involved cutting out several complete bars from the final section to shorten it by around two or three minutes. The very end involved turning up the reverb in the mix whilst fading out the track. The title is stolen from an exhibition by Kerry Tribe seen at the Arnolfini Gallery in Bristol in 2010, in which one exhibit was made of a single tape loop that snaked around one whole floor of the gallery. (8)

‘On the Margins of Forgetfulness (The Sleep of Wakefulness)‘ (whose title I cannot remember the origins of, other than it appearing as two separate notes discovered in a notebook whilst searching for possible titles) began as a forgotten guitar part found on an old four-track borrowed from a friend years ago. The guitar part was recorded in 2012 in my room in a shared house in Bath. I added glockenspiel, auto-harp, shaker and tambourine before setting about hiding the source sounds with layers of treatments and delay.

‘Sinking Into Nothing, Being Without Trace, No Flowers Please’ was originally three separate tracks, none of which were quite working for various reasons. I had been thinking about attempting to merge tracks together to make longer, more varied electronic pieces for some time, maintaining the minimalist theme whilst increasing the interest for the listener, and this track has become my first effort at this. The result is an improvement on the three original starting points.

The titles may appear to all be negative but this is unintentional. I read a lot, and as I read I find pleasing words or interesting sounding phrases, and I note them down. Then when it comes to finding titles I will go back through these notebooks and pick words or phrases which I think reflect the mood of the piece, or when combined with the piece add to it’s meaning or increase it’s ambiguity. The words and phrases have been so far removed from their sources, by time and an imperfect memory, that their original context has been stripped from them and they are cleansed and ready for new meanings and associations to be attached. Sometimes, as in ‘Sinking Into Nothing, Being Without Trace, No Flowers Please’, which may well sound somewhat funereal, I am attracted to the words through a kind of black humour. I am well aware of the negative connotations, but I find it funny.

You may have noticed that the majority of the references I cite as musical influences stem from the 1970’s: David Bowie; Brian Eno; Neil Young; Simon and Garfunkel; Nick Drake, etc., and I do believe that as far as recorded music goes this was something of a Golden Age, but ‘Dream Songs’ doesn’t sound like it’s from the 70’s, it is an album that could only have been made in the early 21st Century, with the strange Blade Runner style mash up of acoustic, analogue and digital technology that is now so available and affordable that anyone can make music and release it, ‘Making Do and Getting By’ (9) as human beings are wont to do. It is now easier than ever to record and release music, it is however harder than ever to get anyone to listen to it.

The Erratic is my musical means of creative release (I have others. I write and make art, to equal indifference). I have no expectations. I have given more music away than I am ever likely to sell. But that’s ok. I make it for myself. It gives me pleasure. If other people listen, that’s a bonus. If you listen and say you like it, I probably won’t believe you. I don’t play live. I don’t wish to engage with an audience. There is no reason for you to care. If you have listened, and if you have read this, then thank you. That is all. Why should there be more?

CJ Robinson – January 2016

1 Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bIxDn-Gcu5k (Accessed: 18th December 2015) – Although I don’t feel this quote describes my own music I would hope it could evoke a similarly poetic response in some listeners.

2 “An Interview with John Berryman” conducted by John Plotz of the Harvard Advocate on Oct. 27, 1968. In Thomas, H. Ed., Berryman’s Understanding: Reflections on the Poetry of John Berryman, (Boston: Northeastern UP, 1988)

3 Ginsberg, A., Howl and Other Poems (San Francisco: City Lights, 1956)

4 Yates, R., Eleven Kinds of Loneliness (London: Vintage Classics, 2008)

5 Beckett, S., Waiting for Godot, (London: Faber and Faber, 1988)

6 This relationship is also documented on the 2014 album ‘A Soft Light’, and the ‘And’ EP of 2015, in particular the song ‘I Know We Can Beat Them’ (Available at: www.theerratic.bandcamp.com )

7 Cox, B., Human Universe, (BBC, 2014)

8 Tribe, K., Dead Star Light, (Bristol: Arnolfini; London: Camden Arts Centre; Oxford: Modern Art Oxford, 2010)

9 Wentworth, R., Making Do and Getting By (Photographs, 1973-ongoing)

Grinlow Art Trail 2015

“As Above So Below”

an artwork by CJ Robinson

made for the second Grinlow Art Trail, held in Grinlow Woods, Buxton, Derbyshire,

on Saturday 18th & Sunday 19th July 2015

CJ Robinson interviewed by James Merrick

James Merrick: So, maybe we should start with a brief description of the piece. “As Above So Below” is a grid of variably sized mirrored tiles arranged into a four foot square, placed on a roughly forty-five degree slope next to a path in a public woodland. What were your immediate aims for the piece?

Chris Robinson: Well, I suppose I was hoping for a transformation of the familiar, an unusual view of something we are so used to that we maybe take it for granted without even realising we are taking it for granted, and so offer an opportunity to shake us out of our complacency and consider it afresh. I mean, I live locally and I walk through these woods regularly, and I like to think I appreciate them, but I’m sure sometimes I’m so wrapped up in my day-to-day life and problems that go with that, that I don’t really see the woods. I know them, I look at them, but I don’t really see them.

JM: There’s a lightness of touch to the work, a simplicity, that automatically evokes Minimalism, and in particular the square grid pieces of Carl Andre. Was that intentional?

CR: Of course. I admire the work of Carl Andre, and Minimalism generally. One can’t lay squares on the ground calling it an artwork and not reference Carl Andre. And I suppose in my own work I’m increasingly looking for the simplest means to create the most profound transformation. That’s what I admire about Minimalism, it’s ability to address complex ideas with the lightest of touches. There’s a reduction, a stripping away of the unnecessary, in a search for the essential. There’s a purity to the best of Minimalism – the artist, by the subtlety of his or her intervention, is almost absent from it.

JM: And I can also see references to James Turrell’s Skyrooms in the way the mirrors frame a small section of the woods and sky, drawing attention to and inviting a slow contemplation of a possibly overlooked, or neglected, detail.

CR: Yes, I’m glad you saw that. I didn’t consciously reference James Turrell, but I am a fan. I would love to visit his volcano in the states. The work also references that whole Land Art thing of Andy Goldsworthy and Richard Long, or the geometry-in-nature of Robert Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty”, or Agnes Denes’ “Tree Mountain”.

JM: We should talk about the title as well, which inevitably brings us into the realms of Conceptual Art, where a carefully chosen object and title can combine to provoke all sorts of associations and meanings. Do you want to tell us where the title comes from and why you chose it for this piece?

CR: “As Above So Below” comes from the opening section of “The Emerald Tablet”, a rather strange and esoteric ancient text attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, who may or may not have been the Greek equivalent to the Egyptian god of wisdom, Thoth. Anyway, Trismegistus (which means ‘thrice great’) developed the magical system of Hermeticism, which went on to influence the whole of Western occultism. People as diverse as Isaac Newton, William Blake and Aleister Crowley were, to varying degrees, followers, or, in the cases of Newton and Crowley, practitioners. Now, I’m not particularly interested in occultism or magic, I am a rationalist and a materialist, but I appreciate how the natural world, and in particular here in this instance a woodland, can heighten that sense of the spiritual and pagan in a person, it can heighten our wonder at the natural world and our place within it. But it is what that first section of the Emerald Tablet says and how it links to me placing mirrors in a wood that I’d like to draw attention to here. And in particular the phrase “as above so below” which in this tradition is said to “hold the key to all mysteries.”

JM: Maybe at this point it would be useful to insert the relevant quote before carrying on?

CR: Yes, of course.

This comes from a website called themystica.com:

“’That which is above is the same as that which is below’…Macrocosmos is the same as microcosmos. The universe is the same as God, God is the same as man, man is the same as the cell, the cell is the same as the atom, the atom is the same as…and so on, ad infinitum.”

So, contained in this quote is the idea that the really, really big looks the same as the really, really small.

JM: Like Blake’s “to see a world in a grain of sand”.

CR: Exactly. In that poem Blake was directly referencing “The Emerald Tablet”. And it is an idea that science has only relatively recently discovered. An atom has a similar structure to a solar system or a galaxy for example. In fact we find the natural world has managed to produce infinitely varied complexity out of the simplest of rules.

JM: We’re entering the realms of chaos theory here aren’t we, along with fractals and particle physics.

CR: Indeed we are. The Mystica goes on to say with reference to ‘as above so below’, as well as Hermeticism more generally:

“To the magician the magical act, that of causing a transformation in a thing or things without any physical contact, is accomplished by an imaginative act accompanied by the will that the wanted change will occur. The magical act and imaginative act becomes one and the same. The magician knows with certainty that for the change to occur he must will it to happen and firmly believe it will happen. Here it may be noted that magic and religion are akin: both require belief that a miracle will occur.”

I would like to posit that were we to replace the words ‘magician’ and ‘magical act’ with the words ‘artist’ and ‘artistic gesture’ this paragraph would still hold true. So if the magical act can cause transformation without physical contact, and the artistic gesture (say, by placing mirrors in a wood) can do the same, we are left with an equation:

if magic = transformation, and art = transformation, then art = magic

And I would go further and suggest you could also replace those words with the words ‘scientist’ and ‘scientific experiment’.

JM: So, science and art are both modern day equivalents to magic and religion?

CR: Yes, it’s where we look for meaning in the world.

With that in mind I will leave you with one more quote from The Mystica, and, again, try replacing the word ‘magician’ with either ‘artist’ or ‘scientist’, and the word ‘witchcraft’ with either ‘art’ or ‘science’ and see what effect, if any, this has on the paragraph’s meaning:

“To bring about such a change the magician uses the conception of ‘dynamic interconnectedness to describe the physical world as the sort of thing that imagination and desire can effect. The magician’s world is an independent whole, a web of which no strand is autonomous. Mind and body, galaxy and atom, sensation and stimulus, are intimately bound. Witchcraft strongly imbues the view that all things are independent and interrelated.’”

JM: And all that just from sticking some mirrored tiles in a wood. Chris Robinson, thank you very much.

CR: Thank you.

James Merrick is an independent writer, curator and critic. A series of his essays can be viewed at: www.jamesmerrick.blogspot.com and his self-published books can be viewed and bought from: www.blurb.co.uk/user/JamesMerrick

Cities and Memory – Oblique Strategies

April sees the launch of Cities and Memory’s Oblique Strategies project, to which I have made a contribution with a remix of a field recording from Birmingham New Street Station.

“Cities and Memory: Oblique Strategies sees more than 60 artists all over the world reinterpret and reimagine field

recordings, using Eno and Schmidt’s Oblique Strategies cards as creative inspiration for their reworking of the original source sound.

recordings, using Eno and Schmidt’s Oblique Strategies cards as creative inspiration for their reworking of the original source sound.

Each artist selected a source field recording to reimagine, and was then allocated two Oblique Strategy cards, which they used to guide, inform and inspire their reimagined version of the recording.

Thus, the project builds a whole world of new sounds, created and divined by chance and oblique inspiration.”